Are data trusts trustworthy?

Data is vital to health innovation but there remains a common feeling of mistrust in those who hold that data. Why?

4 July 2023

Data is vital to health innovation and a significant barrier to sharing data is lack of trust – this may be on the part of the public but other stakeholders, including researchers and companies investing in such innovation, have their own concerns. These include misrepresentation of their datasets or how to protect their intellectual property among others. Data trusts are just one form of data intermediary that have been recommended as a way of tackling such barriers to data sharing.

In healthcare we are most familiar with the term ‘trusted research environment’ (TRE). The term ‘secure data environment’ also crops up in the Government’s Health Data Strategy and seems to be being used synonymously with TREs. There is evidently a pattern of data stewardship and sharing vehicles using language which implies that they are a particularly trustworthy means of sharing data, such as ‘trusted research environments’, ‘data trust’ and ‘secure data environments’.

These entities are not interchangeable. The rights, limitations and operating infrastructure granted to data trusts and TREs are different as each has a demonstrably different purpose. What they have in common is language that implies they are deserving of trust: a special status of trust in the minds of stakeholders. So, just what are the features that confer the special status of ‘trustworthiness’?

How to be trustworthy

Baroness Onora O’Neill suggests that trustworthiness is earned by those who are reliably honest and competent. She indicates that the focus should be on trustworthiness as opposed to its end product ‘trust’ and consequently, that it is the humans (operating and overseeing trusts) that are the focus of trustworthiness. Interestingly for data trusts, the trust-evoking language seems to be directed towards the trustworthiness of the system, not specifically human actors.

Appropriate processes and safeguards are important for insuring against system or human failure and compensating harm. These features play an important role in compelling humans to act in a trustworthy manner whether by ‘carrot or stick: so, what features are necessary to encourage the humans operating them to act reliably, honestly and competently?

What is a data trust?

There is no legal or written standard on the core features of a data trust. This means there is little oversight of what guarantees their trustworthiness and ample room for diverging practices and standards.

The Open Data Institute (ODI) defines the features of a data trust by drawing on the concept of legal trusts that have existed for centuries in the UK. The ODI states they must have,

- a clear purpose

- a legal structure (trustor, trustees with fiduciary duties and beneficiaries)

- some rights and duties over stewarded data

- a defined decision-making process

- a description of how benefits are shared

- and that they must have sustainable funding

Setting out the structure of a legal trust helps to understand the overall relationship structure of most data stewardship entities, including trusted research environments. But there are differences, particularly where governance of a data intermediary is done through a means other than trust law, for example by contract – which can often be the case.

Loosely, a legal trust is a web of specified legal relationships between identifiable parties over identifiable property. Those relationships set out who benefits from the trust property (beneficiaries), who has duties to ensure that the trust deed (a binding document determining how the property is to be managed) is carried out (trustees) and a trustor (the person who created the trust for the benefit of its beneficiaries).

What is interesting about using a legal trust for data stewardship is that it gives rise to specific legally binding obligations of trust (fiduciary duties) on those managing its property (the trustees). As such, the penalties on the trustees for failing to carry out the trust deed are generally more severe than contractual obligations and the legal enforcement actions are more extensive than legal relationships governed under other legal frameworks.

Trustees are equally liable under trusts law and where only one breaches their duties, all can be sued regardless of wrongdoing. In some circumstances, criminal sanctions can also be imposed. Consequently, those who accept the role of a trustee generally take on more onerous legal obligations than under, for example, contractual legal relationships. Their subsequent vulnerability chimes with O’Neill’s concept that voluntarily adopting a more ‘vulnerable’ position, as trustees would be here, is an indicator of trustworthiness. It is important to note that here it is the structure and powers of a legal trust that arguably asks this vulnerability of its trustees highlighting the importance of trustworthy features.

What is a TRE and what features support trustworthiness?

The health sector is more familiar with a different data stewardship and sharing structure known as trusted research environments (TREs). Despite the implication of their name, TREs are not commonly governed by trust law and the features to ensure TREs are run in a trustworthy manner are less clear. Existing guidance tends to focus on ensuring that researchers accessing TREs are trustworthy, rather than those running and overseeing such structures.

TREs can be defined as a computing environment that can be accessed remotely by approved researchers to analyse its data library. Such environments have enhanced security measures to ensure only accredited researchers can gain access, oversight measures to track research activities and purposes, and measures that ensure the data cannot be exported from the environment, as well as deidentification measures to prevent data subjects being identified in resulting research outputs.

As with legal trusts, TREs also involve a web of relationships between the approved researchers, the data subjects and those running the TRE (overseeing research activities on its data). There are therefore both rights and limitations to what different parties can do. However, any breach would be governed under contract as opposed to trust law.

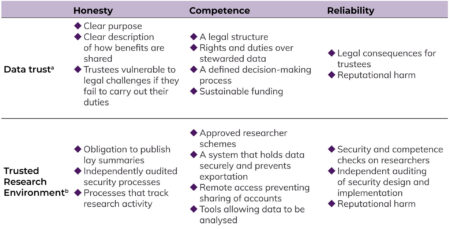

Table 1 What features suggest honesty, competence and reliability? (Mapping the ODI and UK Health Data’s listed features onto O’Neill’s features of trustworthiness)

By adopting Onora O’Neill’s criteria or indicators of trustworthiness, it is clear that both putative data trusts and TREs have features that may support trustworthiness. To fully assess ‘trustworthiness’ requires a detailed analysis of specific structures and institutions but the core features of each structure could be mapped in a similar way against such a framework (Table 1) for further assessment.

Do we need a set of standards?

Whilst several bodies have sought to outline core features of data trusts and TREs (what are these vehicles, how are they structured, how are they to be run etc) the greater clarity and consistency offered by centralised standards would be beneficial. There is at least an exacerbated risk that a scandal involving one poorly governed TRE or data trust could undermine trust in them and their potential to mitigate data sharing challenges, which could provide a serious blow to the Government’s efforts to advocate their use.

There are other regulatory challenges that need to be addressed. A less noted but suggested feature is independence. For example, the recently approved EU Data Governance Act advocates the use of data intermediaries (a collective term for data stewardship vehicles) but suggests that they must be independent from profit-making activities of parent organisations. How, if at all, the UK’s data regulatory bodies will define or even insist such vehicles are independent is yet to be seen. Interestingly, within O’Neill’s framework, independence may not be necessary in all contexts if there is honesty about the relationships and interests involved.

A more practical and currently unanswered issue is how the individuals overseeing and running these intermediaries will be insured and compensated given the vast reputational, legal and ethical risks they will be absorbing on behalf of those they operate for.

Whatever core features and definitions are suggested, the regulatory focus needs to be on building features that ensure that the people operating and using them are trustworthy. One potential approach might be a certification scheme or code of conduct under the UK GDPR in collaboration with the ICO (co-regulatory standards) for approved data trusts, TREs or other intermediaries. The Government’s response to the Data Protection Consultation suggests that they are currently considering clarifying whether non-legislative action is needed and intend to keep an eye on how intermediary markets develop. This blog provides an example of where guidance is needed and provides a possible method for assessment.

Table 1 – references

a: Data trust